My summer has been going pretty much the way every other season has been going for the last year, which is to say that, for the most part, if it can go wrong it will go wrong. That applies to things both petty (all the shoes I wear to work are falling apart) and more serious (my apartment is a disaster story and my cat is broken), but to top it all off, I'm in a total reading rut. To be fair, I've actually been having decent luck on the nonfiction front. It's just that my feelings about the fiction I've been reading lately have ranged from indifference, to irritation, to irrational loathing. I have to admit, I was even more than a little relieved to read that other people are also experiencing the reading doldrums this summer. But unfortunately, as is usually the case with the whole misery-loves-company thing, that hasn't made my own problem (or my desire to whine about it) go away. I thought I'd write then, about the last novel I completely enjoyed.

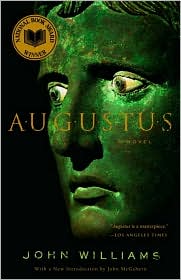

My summer has been going pretty much the way every other season has been going for the last year, which is to say that, for the most part, if it can go wrong it will go wrong. That applies to things both petty (all the shoes I wear to work are falling apart) and more serious (my apartment is a disaster story and my cat is broken), but to top it all off, I'm in a total reading rut. To be fair, I've actually been having decent luck on the nonfiction front. It's just that my feelings about the fiction I've been reading lately have ranged from indifference, to irritation, to irrational loathing. I have to admit, I was even more than a little relieved to read that other people are also experiencing the reading doldrums this summer. But unfortunately, as is usually the case with the whole misery-loves-company thing, that hasn't made my own problem (or my desire to whine about it) go away. I thought I'd write then, about the last novel I completely enjoyed.There's nothing particularly original about what John Williams does in Augustus. That's not a complaint. I'm just saying that the epistolary novel has been around for about as long as the novel itself, at least in Western literature, and to write about Augustus Caesar is to go down a well-travelled path. But that doesn't matter here.

Augustus covers, roughly speaking, three separate subjects in the life of Augustus Caesar: his rise to power, the exile of his daughter, and his death. John Williams tells the story through letters, diaries, and memoirs. In the first two sections of the novel, these are the works of Augustus' contemporaries. Only in the final section does Williams give voice to the emperor himself.

In his author's note Williams wrote,"if there are truths in this work, they are the truths of fiction rather than of history." Augustus isn't meant to be a biography, fictional or otherwise, and Williams isn't interested in presenting facts. He understands the limits of fiction and nonfiction and chooses not to tell us what happened or why but instead concerns himself with an exploration of power and duty and the sacrifices those twin gods demand. He illuminates the interior worlds that history cannot show us with a broad-minded empathy and in doing so tells us something about who we are--our loves, our needs, our friendships, the way we govern ourselves and the way we are governed--without asking the novel to carry a greater burden than it can bear.

rather than of history." Augustus isn't meant to be a biography, fictional or otherwise, and Williams isn't interested in presenting facts. He understands the limits of fiction and nonfiction and chooses not to tell us what happened or why but instead concerns himself with an exploration of power and duty and the sacrifices those twin gods demand. He illuminates the interior worlds that history cannot show us with a broad-minded empathy and in doing so tells us something about who we are--our loves, our needs, our friendships, the way we govern ourselves and the way we are governed--without asking the novel to carry a greater burden than it can bear.

Augustus covers, roughly speaking, three separate subjects in the life of Augustus Caesar: his rise to power, the exile of his daughter, and his death. John Williams tells the story through letters, diaries, and memoirs. In the first two sections of the novel, these are the works of Augustus' contemporaries. Only in the final section does Williams give voice to the emperor himself.

In his author's note Williams wrote,"if there are truths in this work, they are the truths of fiction

rather than of history." Augustus isn't meant to be a biography, fictional or otherwise, and Williams isn't interested in presenting facts. He understands the limits of fiction and nonfiction and chooses not to tell us what happened or why but instead concerns himself with an exploration of power and duty and the sacrifices those twin gods demand. He illuminates the interior worlds that history cannot show us with a broad-minded empathy and in doing so tells us something about who we are--our loves, our needs, our friendships, the way we govern ourselves and the way we are governed--without asking the novel to carry a greater burden than it can bear.

rather than of history." Augustus isn't meant to be a biography, fictional or otherwise, and Williams isn't interested in presenting facts. He understands the limits of fiction and nonfiction and chooses not to tell us what happened or why but instead concerns himself with an exploration of power and duty and the sacrifices those twin gods demand. He illuminates the interior worlds that history cannot show us with a broad-minded empathy and in doing so tells us something about who we are--our loves, our needs, our friendships, the way we govern ourselves and the way we are governed--without asking the novel to carry a greater burden than it can bear.There's something restorative about an author for whom writing is a means of communicating and not a chance to show off their talent for linguistic acrobatics. Williams style is modest and draws no attention to itself. His writing is clean and clear, neither spare nor overwrought but perfectly balanced. This quality seems most refined, appropriately enough, toward the end of the novel, when Williams gives us Caesar through his own eyes.

Letter: Octavius Caesar to Nicolaus of Damascus (A.D. 14)August 9Though it was nearly sixty years ago, I remember that afternoon on the training field when I got the news of my Uncle Julius's death. Maecenas was there, and Agrippa, and Salvidienus. One of my mother's servants brought me the message, and I remember that I cried out as if in pain after I read it.But at that first moment, Nicolaus, I felt nothing; it was as if the cry of pain issued from another throat. Then a coldness came over me, and I walked away from my friends so that they could not see what I felt, and what I did not feel. And as I walked on that field alone, trying to rouse in myself the appropriate sense of grief and loss, I was suddenly elated, as one might be when riding a horse he feels the horse tense and bolt beneath him, knowing he has the skill to control the poor spirited beast who in an excess of energy wishes to test his master. When I returned to my friends, I knew that I had changed, that I was someone other than I had been; I knew my destiny, and I could not speak to them of it. And yet they were my friends.

At this point in the book, we have witnessed the scene where Augustus learns of Julius Caesar's death before. Williams has unfurled the story of the emperor's life already. Early on this particular moment was described by Salvidienus Rufus. He describes a cry, "grating and loud and filled with uncomprehending pain, like the bellow of a bullock whose throat has been cut at a sacrifice," and Octavius alone, "a slight, boyish figure walking on the deserted field, moving slowly, this way and that, as if trying to discover a way to go." But now, with Augustus at the end of his life, we reflect back with all the clarity of hindsight. It's an elegant conceit, and effective because it feels utterly natural. This moment, horrible and marvelous and world-changing, deserves to be revisited and enriched. In his old age, Williams's Augustus can see so clearly, he has become a kind of oracle who knows what will come of all he has built, the limit of his power, and accepts it. It's a beautiful thing in its way.

It's surprisingly hard for me to write about Augustus. Here I have this beautiful object in my hands, this work that is complete and whole, and I find that I don't want to pick at it too much. I've been working on this post for much longer than I'd like to admit (because something with this much time devoted to it ought to be less half-assed). So it goes.